This article traces the history of daydreaming, explains its three recognised styles, and looks at the benefits associated with this practice.

Jump to section:

Introduction

Daydreaming. Mind-wandering. Thought intrusions. Task-irrelevant thoughts. Inattention. Stream of consciousness. Spontaneous thought. Lapse of focus. We have numerous phrases to describe what may positively be called a state of reverie, or alternatively, denounced as the main obstacle to passing that course or getting that promotion.

Mind wandering and daydreaming: Is there a difference?

William James, the “father of American psychology” (Kaufman & Singer, 2011), was an early advocate of studying stream of consciousness, which he called “stream of thought” and understood as an important topic for psychology. For James, daydreaming was not just “mind-wandering”, not just a shift in attention away from an ongoing mental or physical task toward new sensory reactions in the person’s physical, social, or bodily environment. Rather, the shift in attention away from the ongoing task was toward a series of thoughts derived from long-term memory, frequently taking a narrative form (Kaufman & Singer, 2011). This difference turns out to be significant:

- Shift in attention from a task to a new sensory reaction in the environment VERSUS

- Shift in attention from a task to thoughts coming from long-term memory.

Jerome Singer and the Imaginal Processes Inventory

William James was not the only one to assert the importance of studying the mind “from within.” Influenced by James, the late Jerome Singer, psychologist and director of Yale’s clinical psychology program for over four decades, wrote extensively on the mind-wandering state that he came to call daydreaming. He was convinced that systematic, scientific experimentation was crucial to exploring the inner mind, and along with associates such as John Antrobus and Eric Klinger, began interviewing adults about their attention lapses, and the circumstances under which they came into daydreams.

Daydreaming is common; iconoclastic stance on adaptiveness

These interviews and experiments were notable for multiple reasons. First, they were occurring at a time in the 1960s when most American psychologists associated fantasy and daydreaming with psychopathology. Yet Singer and his colleagues, in speaking with or surveying “normal” (non-clinical) people, came to find out that mind wandering is a normal, hugely widespread, and sometimes adaptive human phenomenon – and it occupies a sizeable portion of waking life (McMillan et al, 2013; Kaufman & Singer, 2011).

Methods still in use

Second, the various methods Singer and associates used are still employed in modern research, over a half-century later: a remarkable occurrence when we reflect that Singer did not have access to fMRI, PET scans, and certain research techniques that have only been developed in the last decade or two (McMillan et al, 2013).

Daydreaming styles emerge as valid factors

A third reason for which the interviews and experiments being conducted by Singer and associates were notable was that three distinctive styles emerged which were validated by factor analysis. Singer and Antrobus developed the Imaginal Processes Inventory, a 344-item questionnaire asking about aspects such as daydream frequency, emotional content, sexual content, visual imagery, acceptance of the mind wandering, and distractibility (Singer & Antrobus, 1966, revised in 1970). A short version was developed later. Factor analysis of both the original and the short version showed three broad daydreaming styles: positive constructive daydreaming, guilty-dysphoric or guilty-fear-of-failure daydreaming, and poor attentional control. The validity of these three styles/factors has been demonstrated repeatedly in the last 40 years in a broad range of respondents (McMillan et al, 2013).

The perspective of modern research: Daydreaming as just a mind-control failure?

This positive stance for some “mind wandering” was significant given the larger research picture. Even in the last two decades, most studies have portrayed daydreaming as a cognitive control failure (McVay and Kane, 2010). When Mooneyham and Schooler (2013) reviewed the costs and benefits of daydreaming, they identified 29 studies published since 1995 which focused on the costs of mind-wandering. But they only found six studies published during the review period which noted the benefits of mind-wandering.

Why such an imbalance? Singer found that daydreaming is a universal experience, which about 96% of us do throughout the day, for about 47% of the time (Killingsworth and Gilbert, 2010). If the costs are so great and the benefits so low, why do people engage in it so much? The costs seem obvious, but we need to look to the most adaptive of the three styles, positive constructive daydreaming, for benefits. We can understand it in relation to our default mode network and in contrast to the two styles that do not help us.

The three styles of daydreaming

Daydreaming, this refocusing of attention from outward surroundings to one’s inner thoughts and feelings, is said to be triggered when the brain experiences a lack of external stimulation. With no outer task to attend to, we can go into the default mode network which, although not named as the DMN by Singer, was nevertheless observed to be activated “anti-correlationally” (that is: at opposite times) to when a person was focused on a task. Even well before the advent of fMRI, Singer and Antrobus remarked on the apparent competition between internally and externally produced information streams for limited attentional resources (McMillan et al, 2013). Singer and his associates demonstrated through prolific studies that a lack of focus on a set, external task would produce one of these three states.

Guilty-dysphoric daydreaming

This type of daydreaming consists of dense, undesirable emotions such as fear, anger, and guilt. In this anguished daydreaming, the individual creates fantasies that may be obsessive, hostile, or violent, such as taking revenge on a perceived enemy. A guilty-dysphoric daydreamer might continually play internal videos of failing an important upcoming test, or alternatively, reliving a terrible scene from the past, such as being told that their spouse was divorcing them. The neurosis associated with such daydreaming can manifest as depression, anxiety, obsession, hypochondria, or other conditions. Rumination is sometimes regarded as a form of this sort of daydreaming, but not all psychologists agree to call it “daydreaming;” that said, it is observed to use the same neuronal network – the DMN – as positive daydreaming does (Eddens, 2021).

Poor attentional control

This one is different from Singer’s other two types, and perhaps is not aptly called “daydreaming” at all. It involves difficulty in concentrating on a task or a train of thought. It is this style of mind-wandering, when in control, that might mean that we wander away from a set task toward a distracting thought. Shortly, that distracting thought as well may be replaced by another distracting thought, and so on, until we are forced by some external event to come back into focus on whatever task in the external environment we escaped from in the first place (Eddens, 2021).

It is this style of “daydreaming” we flagged when we asked you to note the difference between:

- Shift in attention from a task to a new sensory reaction in the environment AND

- Shift in attention from a task to thoughts coming from long-term memory.

Poor attentional control is obviously the former: just a shift from one distraction to another, while the sole adaptive style of daydreaming is the latter, as below.

Positive-constructive daydreaming

This light-hearted, wishful, positive imagining can foster creativity and assist planning and goal setting, among many other benefits. Here are five chief ways it can help us.

Lessens stress and anxiety. A top benefit is the mental relaxation and capacity for thought exploration that is fostered when we can tune out the noise and stimulation of the external environment. The flow of thoughts in positive-constructive daydreaming enables us to get into an alpha state: a slower wave than the beta waves of ordinary, daily consciousness. The calmness induced can do much to compensate for the increasing sense of burnout in our ever-noisier, attention-commanding lives.

Helps people solve problems. Have you ever noticed how, in trying to work out some problem, you feel quite “stuck” and frustrated, you disgustedly close up shop and go for a walk, only to find after you get back that BINGO: the solution presents itself unbidden with great clarity? Our DMN is particularly active when we are engaging activities such as daydreaming, contemplating past or future, or otherwise introspecting (which you could have been doing on that walk). Our DMN has the specialised task of activating old memories, recombining different ideas, or – through all of that – imagining new, creative solutions. It can do that because it can access data that was not accessible in our normal beta (regular waking) consciousness (Field, 2021; Pillay, 2017; Pressman, 2023)!

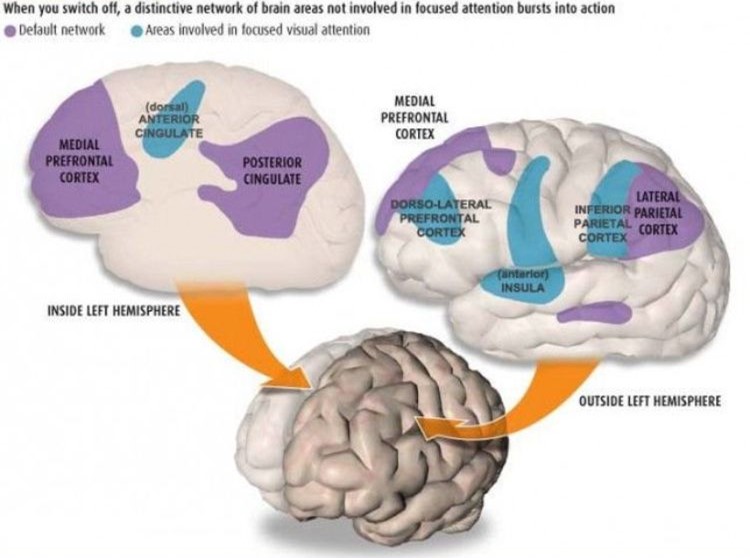

Uses a range of different parts of the brain. Positive-constructive daydreaming, with our DMN in adaptive control, is a case of functional (“wireless”) connectivity, in which different areas of the brain, ones not physically adjacent to one another and which have different “normal” tasks, come together to “play in the band.” Thus, the DMN recruits the medial temporal lobe (memory), the medial prefrontal cortex (theory of mind, for understanding another’s perspective), and the posterior cingulate cortex (integration of various internal thoughts), as well as parts of the parietal cortex, to perform in harmony for our problem-solving, creative efforts, and stress reduction (see Figure 1) (Field, 2021; Pressman, 2023).

Figure 1: The default mode network and areas of focused attention

(Pinterest, n.d.)

Helps people reach goals. One way in which people can experience positive-constructive daydreaming benefits is by engaging intentional, or volitional daydreaming (as opposed to the unintentional mind-wandering of poor attention control).

Used by athletes. This sort is used by athletes and performers to ensure a superior game or performance. It is a form of mental practice to go along with the physical performance on the field or the stage and has been a popular form of structured (purposeful) daydreaming in fields such as sports psychology.

Non-demanding break yields greater success later. Similarly, research published in Psychological Science in 2012 found that when the subjects engaged with an undemanding, non-related task on a break, they were 41% more successful at ensuing tasks than the group that was given a demanding task on their break. They also outperformed a group given no break. They were not necessarily more successful at generating ideas, but at working through existing problems (Baird et al, 2012; Davis, 2017).

Links with mindfulness. Researchers have also found that, while unintentional daydreaming (meaning: not positive-constructive daydreaming) is associated with fidgeting and acting mindlessly, deliberate mind-wandering may be linked with mindfulness. In 2014, on-purpose daydreaming was found to be highly correlated with the aspect of mindfulness known as “non-reactivity to inner experience,” which occurs when practitioners of mindfulness perceive feelings and emotions without having to react to them. Researchers concluded that the more people intentionally mind-wandered, the more mindful they were, and the converse was also true: that unintentional mind-wandering occurred more to those who were less mindfully aware (Gholipour, 2016).

Expands creativity. This adaptive style of daydreaming is correlated with higher levels of creativity. In the Psychological Science study cited above, the demanding task of the subjects was to come up with as many uses as possible for everyday things (e.g., toothpicks and bricks) in just two minutes. Those who daydreamed on a break, rather than continuing to focus on the problem, did better at generating more creative ideas, by that hugely significant margin of 41% (Baird, et al, 2012; Davis, 2017). The mind in focus sees a particular tree; the unfocused (DMN-dominated) mind doing positive-constructive daydreaming can zoom in and out, taking in the entire forest (Field, 2021).

Clearly, history and research have shown that there is much to be said for daydreaming!

Key takeaways

- Daydreaming is a universal experience, occurring in 96% of people for about 47% of the time.

- William James, Jerome Singer, and others took up what has been an iconoclastic stance in proclaiming that off-task “stream of thought” could be helpful for people; they used multiple methods, some still in use, to test their theories empirically.

- Three distinctive styles of daydreaming emerged, validated by factor analysis: guilty-dysphoric daydreaming, poor attentional control, and positive-constructive daydreaming.

- Positive-constructive daydreaming is adaptive in at least five ways. It: (1) lessens stress and anxiety; (2) helps people solve problems; (3) uses different parts of the brain; (4) helps people reach their goals; and (5) expands creativity.

References

- Baird, B.; Smallwood, J.; Mrazek, M.D.; Kam, J.W.Y.; Franklin, M.S.; & Schooler, J.W. (2012). Inspired by distraction: mind wandering facilitates creative incubation. Psychol Sci. 2012;23(10):1117-1122. doi: 10.1177/0956797612446024

- Davis, J. (2017). The science of the daydreaming paradox for innovation. Psychology Today. Retrieved on 16 Jan, 2019, from: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/tracking-wonder/201708/the-science-the-daydreaming-paradox-innovation

- Eddens, A. (2021). Daydreaming: How and why people daydream? Study.com. Retrieved on 13 April, 2023, from: https://study.com/learn/lesson/daydreaming-psychology.html

- Field, B. (2021). 5 positive effects of daydreaming. Very Well Mind. Retrieved on 12 April, 2023, from: https://www.verywellmind.com/positives-about-daydreaming-5119107

- Gholipour, B. (2016). The right kind of daydreaming. Huffington Post. Retrieved on 15 April, 2023, from: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/daydreaming-the-right-way_n_57965337e4b02d5d5ed25e93?ec_carp=8978493911129999009

- Kaufman, S.B., & Singer, J.L. (2011). The origins of positive-constructive daydreaming. Scientific American. Retrieved on 12 April 2023, from: https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/guest-blog/the-origins-of-positive-constructive-daydreaming/

- Killingsworth M. A., Gilbert D. T. (2010). A wandering mind is an unhappy mind. Science 330 932–932 10.1126/science.1192439 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan RL, Kaufman SB, Singer JL. (2013). Ode to positive constructive daydreaming. Frontiers in Psychology. 2013 Sep 23;4:626. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00626. PMID: 24065936; PMCID: PMC3779797.

- McVay J. C., Kane M. J. (2010). Does mind wandering reflect executive function or executive failure? Comment on Smallwood and Schooler (2006) and Watkins (2008). Psychol. Bull. 136 188–189 10.1037/a0018298 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mooneyham B. W., Schooler J. W. (2013). The costs and benefits of mind-wandering: a review. Can. J. Exp. Psychol. 67 11–18 10.1037/a0031569 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pillay, S. (2017). Your brain can only take so much focus. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved on 6 April, 2023, from: https://hbr.org/2017/05/your-brain-can-only-take-so-much-focus

- Pinterest. (n.d.). Image of default mode network and focused attention brain regions. Pinterest. Retrieved on 12 April, 2023, from: https://www.pinterest.com.au/pin/569775790348620329/

- Pressman, P. (2023). Understanding the default mode network. Very Well Health. Retrieved on 10 April, 2023, from: https://www.verywellhealth.com/what-is-the-default-mode-network-2488818