This article explores the diagnostic criteria for autism spectrum disorder, what the term “spectrum” really means, and how to recognise undiagnosed autism in your adult clients.

Jump to section:

Introduction

In the first article in this series (Neurodiversity, Neurodivergence and Being Neurotypical), we explored neurodiversity and some of the strengths, talents and specialist skills of neurodivergent clients. We ended the article by posing the question: “Could a client be neurodivergent and not know?”

In this article we consider the scenario of adult undiagnosed autistic clients with a focus on challenges that might bring them into counselling or therapy, and signs to help you identify more is going on than the presenting issue.

Diagnostic criteria for Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

Autistic individuals have atypical cognitive profiles, such as impaired social cognition and social perception, executive dysfunction, and atypical perceptual and information processing that derive from atypical neural development (Lai et al., 2014).

The diagnostic criteria set out in the DSM-5-TR and ICD-11 are:

Persistent deficits in reciprocal social communication and social interaction including deficits in:

- Social-emotional reciprocity

- Non-verbal communicative behaviours, and

- Skills for developing, maintaining and understanding relationships, and

Restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviour, interests or activities such as:

- Stereotyped or repetitive motor movements, use of objects, or speech

- Insistence on sameness, inflexible adherence to routines, or ritualised patterns of verbal or non-verbal behaviour

- Highly restricted, fixated interests that are abnormal in intensity or focus, or

- Hyper- or hypo-reactivity to sensory input or unusual interest in sensory aspects of the environment, and

There is significant impairment in personal, family, social, educational, occupational or other important areas of functioning (American Psychiatric Association, 2022; ICD-11, 2023).

ASD can be associated with developmental difficulties including cognitive and language delay. Therefore, specifiers that should be added to a diagnosis include:

- With or without accompanying intellectual impairment, and

- With or without accompanying language impairment (with mild or no impairment of functional language, with impaired functional language or with complete, or almost complete, absence of functional language) (American Psychiatric Association, 2022; ICD-11, 2023).

Isn’t ASD a childhood diagnosis?

ASD is a lifelong neurodevelopmental condition which means that the onset occurs during early childhood (Lord et al., 2022). However, the current diagnostic criteria explicitly indicate that:

- Symptoms may not be apparent until social demands exceed limited capacities (such as in adolescence or adulthood)

- Symptoms may be masked by learned strategies in later life, and

- Behaviour contributing to a diagnosis can be by history or current presentation (American Psychiatric Association, 2022; ICD-11, 2023).

These features support a first diagnosis of ASD in adulthood.

Who are the “lost generation”?

Most research and clinical attention have focused on identifying ASD in early childhood (Daniels et al., 2014; Lai et al., 2014). However, in recognition that autism is a lifelong condition, there is increasing interest in studying development across the lifespan and outcomes in adulthood (Happé & Charlton, 2012; Howlin & Moss, 2012).

The phrase “lost generation” was coined in a seminal 2015 paper published in the Lancet Psychiatry to refer to autistic adults who were not diagnosed as children. The authors, from the Autism Research Centre at the University of Cambridge, describe first diagnosis in adulthood as “an important clinical issue due to the increasing awareness of autism, broadening of diagnostic criteria, and the introduction of the spectrum concept” (Lai & Baron-Cohen, 2015).

What does the “spectrum” in ASD mean?

“If you’ve met one person with autism, you’ve met one person with autism” – Dr Stephen Shore (Flannery & Wisner-Carlson, 2020)

When the DSM-5 was introduced in 2013, a number of previously separate diagnostic labels were grouped under one umbrella as autism spectrum disorder (ASD):

- Autistic disorder

- Asperger’s syndrome or Asperger’s disorder

- Childhood disintegrative disorder, and

- Pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Lai & Baron-Cohen, 2015).

The spectrum concept acknowledges the breadth of individuals who now qualify for the diagnosis under the broadened diagnostic criteria (Lord et al., 2022).

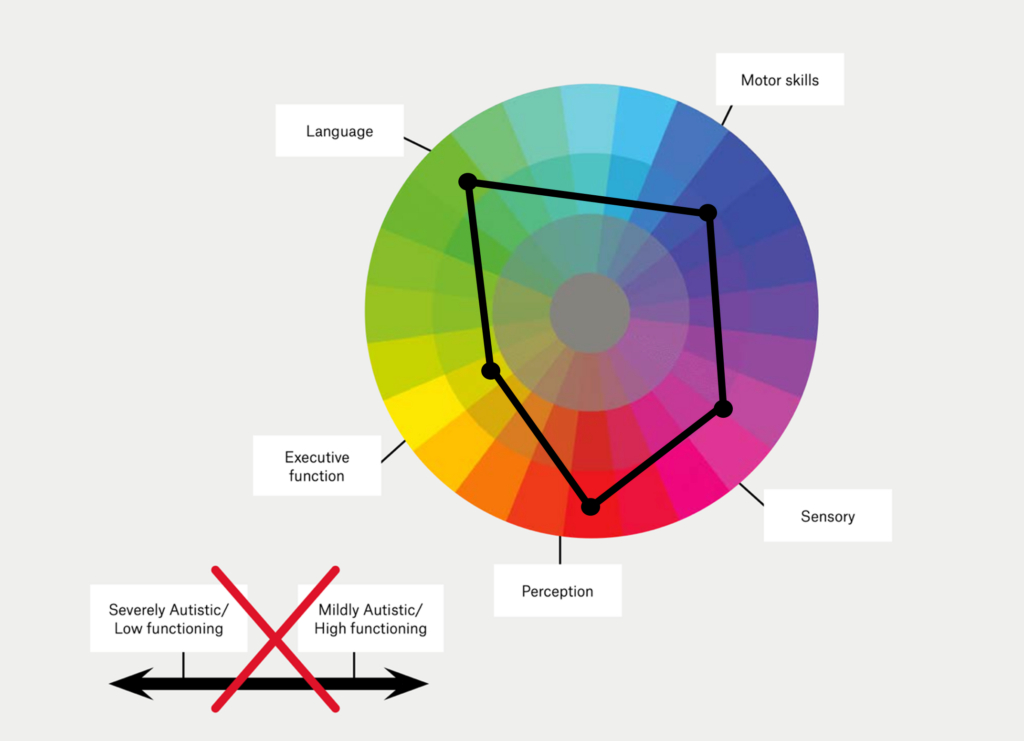

The autism spectrum is often incorrectly conceptualised as a linear scale (Figure 1) with severely autistic clients – those that are considered ‘low-functioning’ – at one end, and those who are mildly autistic or ‘high-functioning’ at the other (Bradshaw et al., 2021). To some extent, this misunderstanding is perpetuated by the current diagnostic criteria specifying severity in terms of support needs (American Psychiatric Association, 2022; American Psychological Association, 2022):

- Level 1: Requiring support

- Level 2: Requiring substantial support

- Level 3: Requiring very substantial support.

However, autistic individuals can have strengths in some areas and challenges requiring supports in others. Therefore, ASD is more accurately represented by a kaleidoscope or colour wheel comprised of language, sensory, executive function, perception and motor skills (Bradshaw et al., 2021; Lord et al., 2022). Each autistic person possesses a unique profile of strengths and needs which can change with age, contextual demands such as the fit between the person and their environment, interventions and level of support (Lai & Baron-Cohen, 2015; Lord et al., 2022).

Figure 1. An example of a correct (colour wheel) and incorrect (linear) conceptualization of the autism spectrum (adapted from Bradshaw et al., 2021)

The term heterogeneity is also used to describe the ways in which autism manifests differently between people who have the condition and also within individuals across the lifespan (Lord et al., 2022). This heterogeneity can make ASD harder to ‘spot’ by helping professionals who have not received specific training. Unsurprisingly, clients with more severe challenges tend to be identified and diagnosed earlier. Individuals without obvious developmental delay and those with more subtle difficulties tend to be diagnosed later (Mandell et al., 2005).

Who does autism affect?

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) has a population prevalence of 1% across all ages (Lai & Baron-Cohen, 2015). Genetics play a key role in the aetiology, along with environmental factors during early development (Lai et al., 2014). Males are four times more likely than females to be diagnosed and are diagnosed earlier (ICD-11, 2023; Lai & Baron-Cohen, 2015). There is growing awareness that autism can present differently in women and girls, leading to the notion of a female phenotype that is underdiagnosed by current diagnostic criteria (Hull et al., 2020).

Recognising undiagnosed autism in your adult clients

The authors of the recent “Lancet Commission on the future of care and clinical research in autism” note:

“Some individuals with autism have average or above average intelligence and language abilities, are university-educated, in professional jobs, in a marriage or partnership, and have children. Others have a severe intellectual disability, little or no functional communication skills, few social relationships outside their immediate family, and require constant lifetime care” (Lord et al., 2022).

The following list provides examples of how you might identify a client from the “lost generation”. Keep in mind that each client with autism will have a different constellation of traits, behaviours and challenges, and also that these are fluid (present sometimes and absent at other times).

Your client may have undiagnosed autism if they:

- Find it hard to initiate conversations.

- Speak in monologues.

- Have difficulty with back and forth conversation.

- Have trouble sharing their thoughts and feelings.

- Have an unusual tone of voice that sounds sing-song or flat and robot-like.

- Speak loudly.

- Use few gestures or facial expressions.

- Display odd, wooden, or exaggerated body language during interactions.

- Display facial expressions, movements or gestures that don’t match what is being said.

- Make little or inconsistent eye contact.

- Appear aloof, indifferent, unusual or unresponsive.

- Find it hard to understand how non-autistic people think or feel.

- Do not understand sarcasm or irony.

- Do not adapt their behaviour according to the social context.

- Say things that others might regard as a faux pas or socially taboo.

- Have been called shy, lazy or rude by others.

- Are socially isolated (related reading: The Stigma and Shame of Loneliness).

- Find it challenging to make and keep friends or intimate partners.

- Have been bullied or victimised, including being in unhealthy relationships or experiencing emotional, physical or sexual abuse.

- Are easily manipulated due to social naiveté.

- Are overcontrolling in interpersonal relationships.

- Demand extremely high standards of friends such as extreme loyalty or form extremely clingy attachments to specific people.

- Find social interactions exhausting.

- Find spending time with autistic people easier and more comfortable than spending time with non-autistic people.

- Have trouble concentrating in group settings because of the mental effort required to monitor social conventions.

- Have lifelong feelings of being different from their peers.

- Have low self-esteem from being unable to be themselves socially.

- Prefer to be on their own.

- Engage in self-stimulatory behaviour (‘stimming’) such as rocking, finger flicking or hand flapping, particularly when excited or under stress.

- Pace or move around repetitively.

- Repeat your words or phrases (echolalia).

- Play the same music, game or video, or read the same book repeatedly.

- Have an intense attachment to particular objects.

- Get anxious or upset about unfamiliar situations and social events.

- Are inflexible in their thinking.

- Are very determined or perfectionistic.

- Follow routines rigidly such as needing to take familiar routes or have meals at set times.

- Are resistant to change or have difficulty with transitions.

- Become distressed by trivial changes in their environment or when things don’t go according to plan.

- Are very rule abiding e.g., when playing games.

- Have a persistent preoccupation with one or more special interests.

- Often talk at length about a favourite subject without noticing that others are not interested or without giving others a chance to respond.

- Find environments that include bright lights or loud noises overwhelming, stressful or uncomfortable.

- Are particularly sensitive or insensitive to heat, cold, pain and textures including clothing.

- Dislike being touched due to sensory sensitivities.

- Have extreme reactions to or rituals involving taste, smell, texture, or appearance of food or excessive food restrictions.

- Have difficulty obtaining or sustaining employment or education.

- Find organising and planning activities challenging.

- Have abnormalities in attention such as hyper focusing and difficulty switching tasks.

- Are not able to carry out some activities of daily living.

- Have problems with anger or aggression (related reading: The Neuroscience of Anger and Anger Management: De-escalating Anger).

- Find emotional regulation challenging and thus experience meltdowns or shutdowns.

- Have previous or current contact with learning disability services.

- Have a history of another neurodevelopmental condition including learning disabilities and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

- Have co-occurring medical disorders, such as epilepsy, sleep, gastrointestinal, metabolic, tic and immune disorders.

- Have atypical motor development e.g., dyspraxia, dysgraphia or poor coordination.

- Have a child who has been diagnosed with ASD (American Psychiatric Association, 2022; Barrett et al., 2015; Crompton et al., 2020; Greaves-Lord et al., 2022; Green et al., 2019; Grove et al., 2016; ICD-11, 2023; Jordan & Caldwell-Harris, 2012; Lai & Baron-Cohen, 2015; Moorhead, 2021; National Autistic Society, 2020; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2023; NHS, 2022; Ochoa-Lubinoff et al., 2023).

Presenting problems in adulthood

Common presenting problems in adulthood include:

- Reactions to social isolation or the social consequences of inappropriate behaviour.

- A breakdown in domestic or work relationships.

- Mental health challenges or diagnoses (Green et al., 2019; ICD-11, 2023; Jadav & Bal, 2022).

Screening and diagnosis

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK has produced a Clinical Guideline titled Autism spectrum disorder in adults: diagnosis and management (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2023). For adults with possible autism who do not have a moderate or severe learning disability, the guideline recommends helping professionals consider using the Autism-Spectrum Quotient – 10 items (AQ-10) questionnaire as a screening tool.

If a person scores 6 or above, or autism is suspected based on clinical judgment (taking into account any past history provided by an informant), NICE recommends offering a comprehensive assessment for autism (or referral to an appropriate service). The diagnostic process will include interviews with informants and the client, and functional assessments (Lai & Baron-Cohen, 2015).

Making a first diagnosis of ASD in adults can be challenging for a variety of reasons including:

- Informants who could provide a reliable and valid developmental history, such as the client’s childhood caregivers, may have passed away, no longer be in contact, have failing memories or experience recall bias.

- The client may have learned strategies to manage their challenges.

- There is a high frequency of co-occurring or overlapping disorders including depression, anxiety, ADHD, OCD, personality disorders and eating disorders (Lai & Baron-Cohen, 2015).

Some clients with ASD, particularly women, have learned how to mask or camouflage their autistic traits and difficulties from others to minimise the visibility of their social difficulties and avoid stigma and discrimination (Cook et al., 2021; Lai & Baron-Cohen, 2015). These compensation strategies – ‘pretending to be normal’ – are commonly described by autistic individuals as exhausting and are linked to an increased risk for anxiety, depression and suicidal thoughts (Bargiela et al., 2016; Cook et al., 2021). A diagnosis of ASD is still appropriate in these instances particularly when such effort becomes unsustainable due to ageing or changing social circumstances (Lai & Baron-Cohen, 2015).

Where to next?

Many community mental health providers report a lack of knowledge and experience, poor competence and low confidence working with adults with autism (Maddox et al., 2020). In the next article in this series (Supporting the Lost Generation of Adults with Autism), we explore what the research indicates about supporting the lost generation by considering challenges to providing effective care and how psychological therapies might need to be adapted.

Key takeaways

- Clients with autism spectrum disorder have ongoing difficulties initiating and sustaining reciprocal social interaction and social communication and have a range of restricted, repetitive and inflexible patterns of behaviour, interests or activities.

- Although ASD is a neurodevelopmental condition with onset during childhood, current diagnostic criteria permit a first diagnosis in adulthood.

- The “lost generation” refers to autistic adults who were not diagnosed as children.

- ASD is a highly heterogeneous condition meaning each autistic person is different.

- The “spectrum” refers to the wide variation in traits, challenges and support needs of individuals with ASD. The spectrum is best conceptualised as a color wheel rather than a line depicting low to high functioning.

- Undiagnosed clients commonly seek therapeutic support for social difficulties, breakdowns in relationships and mental health challenges.

- ASD may be difficult to identify in adults as they have had time to learn compensatory strategies or may be adept at masking their autistic traits and difficulties.

- The AQ-10 questionnaire can be used to screen adult clients for ASD.

Related Articles

- Neurodiversity, Neurodivergence and Being Neurotypical (Part 1)

- Supporting the Lost Generation of Adults with Autism (Part 3)

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). DSM-5 Autism fact sheet. https://www.psychiatry.org/File%20Library/Psychiatrists/Practice/DSM/APA_DSM-5-Autism-Spectrum-Disorder.pdf

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic And Statistical Manual Of Mental Disorders (5th edition, text revision ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

- American Psychological Association. (2022). Autism spectrum disorder. https://www.apa.org/topics/autism-spectrum-disorder

- Autism Research Centre. (2012). Autism Spectrum Quotient – 10 items (AQ-10) (Adult). https://www.autismresearchcentre.com/tests/autism-spectrum-quotient-10-items-aq-10-adult/

- Bargiela, S., Steward, R., & Mandy, W. (2016). The Experiences of Late-diagnosed Women with Autism Spectrum Conditions: An Investigation of the Female Autism Phenotype. J Autism Dev Disord, 46(10), 3281-3294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2872-8

- Barrett, S. L., Uljarević, M., Baker, E. K., Richdale, A. L., Jones, C. R., & Leekam, S. R. (2015). The Adult Repetitive Behaviours Questionnaire-2 (RBQ-2A): A Self-Report Measure of Restricted and Repetitive Behaviours. J Autism Dev Disord, 45(11), 3680-3692. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2514-6

- Bradshaw, P., Pickett, C., van Driel, M. L., Brooker, K., & Urbanowicz, A. (2021). “Autistic” or “with autism”?: Why the way general practitioners view and talk about autism matters. Australian Journal of General Practice, 50(3), 104-108. https://search-informit-org.ezproxy.library.uq.edu.au/doi/10.3316/informit.761324590799585

- Cook, J., Hull, L., Crane, L., & Mandy, W. (2021). Camouflaging in autism: A systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev, 89, 102080. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102080

- Crompton, C. J., Hallett, S., Ropar, D., Flynn, E., & Fletcher-Watson, S. (2020). ‘I never realised everybody felt as happy as I do when I am around autistic people’: A thematic analysis of autistic adults’ relationships with autistic and neurotypical friends and family. Autism, 24(6), 1438-1448. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361320908976

- Daniels, A. M., Halladay, A. K., Shih, A., Elder, L. M., & Dawson, G. (2014). Approaches to enhancing the early detection of autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 53(2), 141-152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2013.11.002

- Flannery, K. A., & Wisner-Carlson, R. (2020). Autism and Education. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am, 29(2), 319-343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2019.12.005

- Greaves-Lord, K., Skuse, D., & Mandy, W. (2022). Innovations of the ICD-11 in the Field of Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Psychological Approach. Clin Psychol Eur, 4(Spec Issue), e10005. https://doi.org/10.32872/cpe.10005

- Green, R. M., Travers, A. M., Howe, Y., & McDougle, C. J. (2019). Women and Autism Spectrum Disorder: Diagnosis and Implications for Treatment of Adolescents and Adults. Curr Psychiatry Rep, 21(4), 22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-019-1006-3

- Grove, R., Roth, I., & Hoekstra, R. A. (2016). The motivation for special interests in individuals with autism and controls: Development and validation of the special interest motivation scale. Autism Res, 9(6), 677-688. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1560

- Happé, F., & Charlton, R. A. (2012). Aging in autism spectrum disorders: a mini-review. Gerontology, 58(1), 70-78. https://doi.org/10.1159/000329720

- Howlin, P., & Moss, P. (2012). Adults with autism spectrum disorders. Canadian journal of psychiatry. Revue canadienne de psychiatrie, 57(5), 275-283. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371205700502

- Hull, L., Petrides, K. V., & Mandy, W. (2020). The Female Autism Phenotype and Camouflaging: a Narrative Review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 7(4), 306-317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-020-00197-9

- ICD-11. (2023). 6A02 Autism spectrum disorder. World Health Organization. https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/437815624

- Jadav, N., & Bal, V. H. (2022). Associations between co-occurring conditions and age of autism diagnosis: Implications for mental health training and adult autism research. Autism Res, 15(11), 2112-2125. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2808

- Jordan, C. J., & Caldwell-Harris, C. L. (2012). Understanding Differences in Neurotypical and Autism Spectrum Special Interests Through Internet Forums. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 50(5), 391-402. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-50.5.391

- Lai, M. C., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2015). Identifying the lost generation of adults with autism spectrum conditions. Lancet Psychiatry, 2(11), 1013-1027. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(15)00277-1

- Lai, M. C., Lombardo, M. V., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2014). Autism. Lancet, 383(9920), 896-910. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(13)61539-1

- Lord, C., Charman, T., Havdahl, A., Carbone, P., Anagnostou, E., Boyd, B., Carr, T., de Vries, P. J., Dissanayake, C., Divan, G., Freitag, C. M., Gotelli, M. M., Kasari, C., Knapp, M., Mundy, P., Plank, A., Scahill, L., Servili, C., Shattuck, P., . . . McCauley, J. B. (2022). The Lancet Commission on the future of care and clinical research in autism. Lancet, 399(10321), 271-334. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(21)01541-5

- Maddox, B. B., Crabbe, S., Beidas, R. S., Brookman-Frazee, L., Cannuscio, C. C., Miller, J. S., Nicolaidis, C., & Mandell, D. S. (2020). “I wouldn’t know where to start”: Perspectives from clinicians, agency leaders, and autistic adults on improving community mental health services for autistic adults. Autism, 24(4), 919-930. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361319882227

- Mandell, D. S., Novak, M. M., & Zubritsky, C. D. (2005). Factors associated with age of diagnosis among children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics, 116(6), 1480-1486. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-0185

- Moorhead, J. (2021). ‘A lot fell into place’: the adults who discovered they were autistic – after their child was diagnosed. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2021/dec/16/adults-discovered-autistic-child-diagnosed-autism

- National Autistic Society. (2020). Stimming – a guide for all audiences. https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/topics/behaviour/stimming/all-audiences

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2023). Autism spectrum disorder in adults: diagnosis and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg142/resources/autism-spectrum-disorder-in-adults-diagnosis-and-management-pdf-35109567475909

- NHS. (2022). What is autism? https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/autism/what-is-autism/

- Ochoa-Lubinoff, C., Makol, B. A., & Dillon, E. F. (2023). Autism in Women. Neurologic Clinics, 41(2), 381-397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ncl.2022.10.006