Therapists who understand how neurodiversity manifests are better equipped to support neurodivergent clients. This article, the first of a 3-part series (read part 2 here, and part 3 here), explores what it means to be neurodivergent and neurotypical.

Introduction

Much like no two fingerprints are the same, recent neuroscientific research shows that no human brains are anatomically identical (Valizadeh et al., 2018). Each of our brains develop and function differently leading to variation in how we think, feel and behave (Prat, 2022). This diversity is reflected by the wide range of individual:

- Intellectual abilities

- Communication skills

- Social skills

- Emotional functioning

- Sensory experiences

- Motor (movement) skills, and

- Learning abilities.

Neurotypical vs neurodivergent

While all brains are unique, there are patterns of development and functioning that are more common, and those that are less common. Neurotypical clients possess the “majority brain”; they process information, experience the world around them and behave in ways that are considered “typical” (Baron-Cohen, 2017; Silberman, 2015).

Individuals whose brains develop and work differently from those of neurotypical people possess “minority brains”; they are considered neurodivergent or neurominorities (Doyle, 2020). Their brain differences may be subtle and undetectable to you or may be very obvious. Individuals who are neurodivergent have strengths and struggles which are different from their neurotypical peers (Cleveland Clinic, 2022).

“Neurodivergence” is a non-medical term. This means that there are no medical criteria or definitions that can be used to diagnose a client as “neurodivergent”, as medical diagnosis focuses instead on a specific disorder that is considered to fall outside the bounds of typical social behaviour or adaptive functioning. However, the following medical conditions are considered to fall under the umbrella of neurodiversity by people who self-identify as neurodivergent:

- Autism spectrum disorder (ASD)

- Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

- Dyscalculia (difficulty with maths)

- Dysgraphia (difficulty writing)

- Dyslexia (difficulty reading)

- Dyspraxia (difficult with coordination)

- Intellectual disabilities

- Sensory processing disorders

- Tourette’s syndrome (Cleveland Clinic, 2022).

The medical model of deficit and disability

The International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) classifies the conditions above as neurodevelopmental disorders. “Neurodevelopmental” means they begin during brain development, that is, prior to the age of 18, regardless of the age at which a client might be diagnosed (ICD-11, 2023). A similar approach is taken in the latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR)

In medicine, the term disorder implies that the natural order has gone awry and that an individual’s biology is dysfunctional in some way (Baron-Cohen, 2017). This language signals a clear deviation from what is considered “normal”. Medicine pathologizes difference by viewing it as a deficit, deficiency, defect or impairment of functioning.

In the medical model, neurodivergence is considered a form of individual disability. Therefore, the goal of treatment is to transform clients into able-bodied and typically developing individuals; in other words, the aim is to “cure” or “normalize” neurodivergence (Dwyer, 2022).

Other models and paradigms

However, there are alternatives to the medical model. In the late 1990s Australian sociologist Judy Singer proposed the term neurodiversity “specifically for an advocacy purpose” to describe the “emerging human rights movement based on the pioneering work of the Autistic Self-Advocacy Movement which was being joined by other neurological minorities with medically-labelled conditions such as ADHD, the “Dys”abilities and Tourette’s syndrome” (Singer, 1998; Singer, n.d.).

The word neurodiversity has two meanings:

- “a biological truism that refers to the limitless variability of human nervous systems on the planet, in which no two can ever be exactly alike due to the influence of environmental factors” (Singer, n.d.), and

- “an advocacy term to name the Neurodiversity Movement” (Singer, n.d.) that promotes equality and inclusion of those with neurological differences (Baumer & Frueh, 2021).

Viewed through the lens of neurodiversity, neurodivergence is simply one form of variation that exists within the broader diversity of all human minds (Pellicano & den Houting, 2022). Neurodivergence can thus be conceptualized as difference rather than deficit.

Neurodiversity is closely aligned with the social model of disability in which disability is not viewed as the result of an individual’s unique characteristics, but rather as the outcome of a person’s physical and social environment not being able to accommodate those characteristics appropriately (Pellicano & den Houting, 2022). Where the medical model poses the question, “How can this client’s disability be reduced?”, the social model asks, “Is the individual disabled, or is their environment disabling?”

Neurodivergent clients face challenges in a society that is often not set up to accommodate their unique ways of being. For example, in school, neurodivergent students may find it difficult to thrive with traditional teaching methods and standardized testing. In the workplace, neurodivergent employees might struggle with the sensory challenges of an open plan space or social demands. Applying a neurodiversity lens to these examples means the focus will be more about adjusting the fit between the person and their environment than about treating a “disorder” (Doyle, 2020). Autism researcher Professor Simon Baron-Cohen (2017) summarises this point nicely: “The notion of neurodiversity is highly compatible with the civil rights plea for minorities to be accepted with respect and dignity, and not be pathologized.”

Abilities, skills and ‘spiky’ profiles

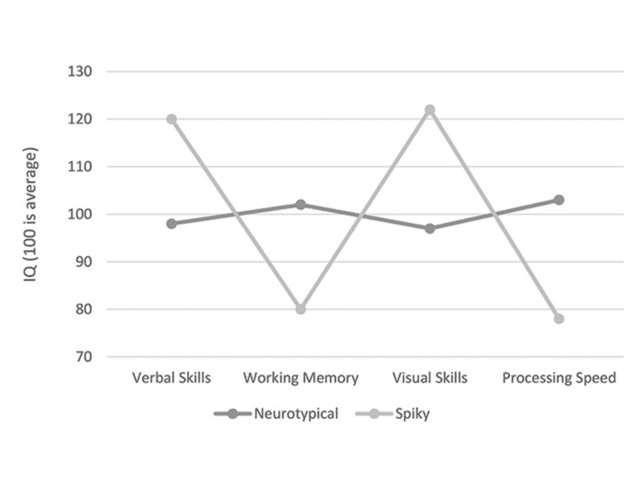

Looking across the entire human population, most humans are “average” when it comes to intellectual skills and the functional skills required for daily living. A small number excel in all areas. Similarly, a small number struggle in all areas. The key point here is that most people’s abilities and skills tend to track together, whether they are average, above average or below average (Doyle, 2020). This flat profile pattern of generalist skills is what we see in neurotypical individuals (Figure 1).

By contrast, clients who have clusters of symptoms that are labelled autism, ADHD, dyslexia and dyspraxia show a different pattern entirely; they excel, are average AND struggle when all intellectual and functional skills are considered (Armstrong, 2011; Astle et al., 2019; Karmiloff-Smith, 2009). This pattern of having specialist skills and talents in some areas, but struggles in other areas, is referred to as a spiky profile. Some researchers now believe that a spiky profile “may well emerge as the definitive expression of neurominority” (Doyle, 2020).

Figure 1. A spiky profile showing examples of skills measured in IQ tests (Doyle, 2020).

Neurodiverse strengths, talents and specialist skills

“The world needs all kinds of minds” – Dr Temple Grandin

Research indicates there is a genetic component to most neurodevelopmental conditions (D’Souza & Karmiloff-Smith, 2017). These conditions are also not rare. If neurodivergence only created disability, that is, only had a downside, we would not expect it to persist in the gene pool (Armstrong, 2015; Doyle, 2020).

A growing number of scientists believe that neurodivergent talents may have conferred specific evolutionary advantages in the past as well as the present (Brüne et al., 2012). It might be that the evolutionary purpose of neurodivergence is to have individuals with specialist thinking skills to balance generalist thinking skills within a group (Doyle, 2020). This idea is captured in a quote from Harvey Blume, the journalist credited with bringing the concept of neurodiversity to the masses through a 1998 article in The Atlantic:

“Neurodiversity may be every bit as crucial for the human race as biodiversity is for life in general. Who can say what form of wiring will prove best at any given moment?” (Armstrong, 2015)

What exactly are these neurodivergent talents? Strengths that have been studied scientifically include:

- Creativity (Leather et al., 2011; White & Shah, 2006)

- Visual-spatial reasoning ability (three-dimensional thinking) (Grant, 2009)

- Attention to detail (Baron-Cohen et al., 2009)

- Hyper systemizing (the ability to recognise patterns) (Baron-Cohen et al., 2009)

- Hyperfocus (Armstrong, 2011)

- Verbal comprehension (Grant, 2009)

- Outstanding memory (Meilleur et al., 2015)

- Entrepreneurialism (Logan, 2009), and

- Specialist individual skills such as reading, drawing and music (Meilleur et al., 2015)

Could a client be neurodivergent and not know?

Although the neurodevelopmental conditions discussed in this article have their onset in childhood, it is possible for clients not to experience significant symptoms until adulthood. This can occur when demands ramp up and exceed their capacities. If a client’s intellectual and functional skills resemble a “spiky profile”, they may be neurodivergent. In a follow-up article, we discuss the “lost generation” of adults with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) – those who were not diagnosed as children.

Key takeaways

- No two human brains work in exactly the same way.

- Neurodiversity refers to the limitless variation among human brains including those that are more common (neurotypical) and those that are less common (neurominorities). Neurodiversity also refers to the human rights movement that promotes inclusion of neurominorities.

- The term neurodiverse should not be used to refer to neurodivergent individuals as neurodiversity includes all human brains.

- Neurotypical clients think, feel and behave in ways that are considered usual by society. Neurotypical individuals tend to have flat profiles in terms of cognitive skills and abilities.

- Neurodivergent clients think, feel and behave differently. They tend to have spiky profiles, meaning specialist talents combined with struggles that may be intellectual or related to everyday living skills.

- The medical model views neurodivergence as a disability to be normalized and treated. The social model of disability views neurodivergence as a difference to be accommodated.

Related Articles

- The Lost Generation of Adults with Autism (Part 2)

- Supporting the Lost Generation of Adults with Autism (Part 3)

References

- Armstrong, T. (2011). The Power of Neurodiversity: Unleashing the Advantages of Your Differently Wired Brain (published in Hardcover as Neurodiversity). Da Capo Lifelong Books.

- Armstrong, T. (2015). The Myth of the Normal Brain: Embracing Neurodiversity. AMA J Ethics, 17(4), 348-352. https://doi.org/10.1001/journalofethics.2015.17.4.msoc1-1504.

- Astle, D. E., Bathelt, J., & Holmes, J. (2019). Remapping the cognitive and neural profiles of children who struggle at school. Dev Sci, 22(1), e12747. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12747

- Baron-Cohen, S. (2017). Editorial Perspective: Neurodiversity – a revolutionary concept for autism and psychiatry. J Child Psychol Psychiatry, 58(6), 744-747. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12703

- Baron-Cohen, S., Ashwin, E., Ashwin, C., Tavassoli, T., & Chakrabarti, B. (2009). Talent in autism: hyper-systemizing, hyper-attention to detail and sensory hypersensitivity. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 364(1522), 1377-1383. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2008.0337

- Baumer, N., & Frueh, J. (2021). What is neurodiversity? https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/what-is-neurodiversity-202111232645

- Brüne, M., Belsky, J. A. Y., Fabrega, H., Feierman, H. R., Gilbert, P., Glantz, K., Polimeni, J., Price, J. S., Sanjuan, J., Sullivan, R., Troisi, A., & Wilson, D. R. (2012). The crisis of psychiatry — insights and prospects from evolutionary theory. World psychiatry : official journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 11(1), 55-57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wpsyc.2012.01.009

- Cleveland Clinic. (2022). Neurodivergent. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/symptoms/23154-neurodivergent

- D’Souza, H., & Karmiloff-Smith, A. (2017). Neurodevelopmental disorders. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Cogn Sci, 8(1-2). https://doi.org/10.1002/wcs.1398

- Doyle, N. (2020). Neurodiversity at work: a biopsychosocial model and the impact on working adults. Br Med Bull, 135(1), 108-125. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldaa021

- Dwyer, P. (2022). The Neurodiversity Approach(es): What Are They and What Do They Mean for Researchers? Hum Dev, 66(2), 73-92. https://doi.org/10.1159/000523723

- Grant, D. (2009). The psychological assessment of neurodiversity. In D. Pollak (Ed.), Neurodiversity in Higher Education (pp. 33–62). Wiley-Blackwell.

- ICD-11. (2023). Neurodevelopmental disorders. World Health Organization,. https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/334423054

- Karmiloff-Smith, A. (2009). Nativism versus neuroconstructivism: rethinking the study of developmental disorders. Dev Psychol, 45(1), 56-63. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014506

- Leather, C., Hogh, H., Seiss, E., & Everatt, J. (2011). Cognitive functioning and work success in adults with dyslexia. Dyslexia, 17(4), 327-338. https://doi.org/10.1002/dys.441

- Logan, J. (2009). Dyslexic entrepreneurs: the incidence; their coping strategies and their business skills. Dyslexia, 15(4), 328-346. https://doi.org/10.1002/dys.388

- Meilleur, A. A., Jelenic, P., & Mottron, L. (2015). Prevalence of clinically and empirically defined talents and strengths in autism. J Autism Dev Disord, 45(5), 1354-1367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2296-2

- Pellicano, E., & den Houting, J. (2022). Annual Research Review: Shifting from ‘normal science’ to neurodiversity in autism science. J Child Psychol Psychiatry, 63(4), 381-396. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13534

- Prat, C. (2022). The Neuroscience of You: How Every Brain Is Different and How to Understand Yours. Dutton.

- Silberman, S. (2015). Neurotribes : the legacy of autism and the future of neurodiversity. Avery.

- Singer, J. (1998). Odd people in: The birth of community amongst people on the “Autistic Spectrum” [Honours thesis, Faculty of Humanities and Social Science, University of Technology, Sydney]. Sydney, NSW.

- Singer, J. (n.d.). Neurodiversity: Definition and Discussion. https://neurodiversity2.blogspot.com/p/what.html

- Valizadeh, S. A., Liem, F., Mérillat, S., Hänggi, J., & Jäncke, L. (2018). Identification of individual subjects on the basis of their brain anatomical features. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 5611. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-23696-6

- White, H. A., & Shah, P. (2006). Uninhibited imaginations: Creativity in adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Personality and individual differences, 40(6), 1121-1131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.11.007