Loneliness has soared in recent decades. It endangers physical and mental health but is often unrecognised as it underlies other concerns and is stigmatised.

Related articles: The Stigma and Shame of Loneliness, Clinical Approaches to Address Social Determinants of Mental Health, Helping Clients Navigate Death Anxiety.

Jump to section

Introduction

Loneliness has accelerated in many parts of the world in recent years. It undermines not only the physical and mental health of the individual experiencing it, but also – when it is widespread – that of the community in which the lonely individuals live. It can be difficult to identify, however, as it is often the underlying problem for other concerns that bring people into the offices of both mental and physical health professionals.

This is the first of a 3-part series about loneliness and how you can help clients assuage it. We offer several fast facts about it, differentiate it from isolation and from solitude, and characterise it as to type. Two quick questions are included for an informal screening to find out if clients are isolated or lonely.

Loneliness fast facts

Social scientists increasingly use the word “endemic” to describe the intensifying trend of loneliness in our world. They are referring to the metrics which indicate that – despite having more or less instant access to our friends and acquaintances through modern communication methods, including social media – we are less connected. Here are statistics that speak to that (in a future article we will add the frightening statistics relating loneliness to health):

- 22% of all adults in the United States say they “often” or “always” feel lonely or socially isolated (that is over fifty-five million people, more than the number who smoke cigarettes and double the number who have diabetes). In Australia, just over 1 in 6 people (16%) reported experiencing loneliness.

- 1 in 3 over forty-five are lonely. And a U.S. Cigna survey reported that 20% of respondents “rarely” or “never” feel close to people. Only 39% of people report feeling “very emotionally connected” to others.

- Young adults are twice as likely to report feeling lonely as those over 65 (phone and social media addiction seems to be a factor). The percentage has increased for ages 15-24 since 2012.

- In Japan, over one million adults meet the official government definition of “social recluse”: hikikomori.

- 33% of adults surveyed in 29 countries worldwide reported experiencing loneliness

- More than 200,000 seniors in the United Kingdom “meet up with or speak on the phone with their children, family and friends less often than once a week” (Murthy, 2020; AIHW, 2024; Reynolds, 2024).

When is it loneliness, and when is it something else?

If you are reading this as a mental health professional, you are unlikely to be surprised by the statement that loneliness is not exactly the fact of being alone.

Loneliness as subjective

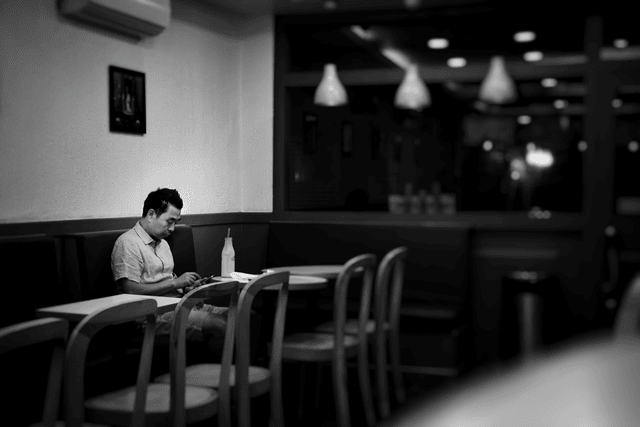

Loneliness is defined as the discrepancy between the quantity and quality of social relationships you have and those you want (Wigfield, 2024). It describes a subjective state. We can illustrate that by posing the theoretical situation of twins, who have the same parents and siblings, attend the same classroom as each other, know the same people as each other, and jointly invite the same people to their annual birthday parties. But one of the twins may feel somehow lonely or relationally unfulfilled, while the other is totally satisfied with their relationships. Thus, the twin that is perceiving the lack of social connections may feel like they are stranded, abandoned, or cut off from the people with whom they belong – even if they are surrounded by other people: the idea of being lonely in a crowd. What’s missing when someone is lonely is the feeling of closeness, trust, and the affection of genuine friends, loved ones, and community (Murthy, 2020). So, lonely is as lonely feels; it is subjective.

Isolation is objective

Conversely, during the COVID-19 pandemic, millions of people were “locked down” for months at a time in many nations of the world. We were told we were not allowed to go out into public spaces except, in some locales, to the local grocery store, where we were masked to the hilt and told to keep our distance from other human beings. Families were not allowed to visit loved ones in nursing homes and hospitals. The mental health of many people dipped during those years. The forced inability to be around others during the pandemic was isolation: an objective experience of not being around other people (although many people subjectively experienced loneliness as well) (Murthy, 2020).

A screening question for social isolation

For a quick way to find out if a client is socially isolated, ask them the following question, offering the response options below the question:

In a typical week, how often do you have contact with family and friends?

___ Every day or almost every day

___ Several times a week

___ About once a week

___ Less than once a week

___ Never

If the client’s answer is “once a week” or less often, they are probably socially isolated. They may be perfectly happy that way, but if they experience the lack of contact as loneliness-engendering, there are multiple approaches (which we offer in a future article) to help alleviate it.

Solitude is not loneliness

Another distinction we need to make is that between loneliness and solitude. Those pursuing creative quests or other work may voluntarily undergo long stretches of time physically alone to deepen into their projects, yet they do not feel lonely at all. Rather, the aloneness is a peaceful opportunity to reflect, restore, and replenish, enhancing their personal growth, creativity, and emotional wellbeing. This state is solitude, not loneliness. Those who are lonely wish to escape the emotional pain of aloneness, whereas solitude, sought by ascetics, monks, and mystics for millennia, is deemed a welcome and necessary chance for introspection and to deepen their connection with the divine.

All of the world’s major religious and spiritual traditions encourage some form of solitude, and it is regarded as a sacred state, one not burdened with shame, as loneliness is. We acknowledge that solitude can allow a person’s individual demons to manifest when both negative and positive emotions surface, but those who engage solitude on a regular basis realise that, in working through issues and gaining clarity on challenges, they strengthen their connections with themselves and – through that – their capacity for relating positively to others. Solitude-engagers thus come to understand the paradox that, while solitude is an alone state, it protects against loneliness (Murthy, 2020).

Characterising loneliness

We can ask whether all loneliness is the same, and the answer is that, no, it is not. Some writers like to differentiate between transient and chronic loneliness.

Transient vs. chronic

A client who has recently undergone a life transition – say, moving to another city, becoming an empty-nester, or losing a beloved life partner to death – may experience a period of reorientation as they establish new links with compatible or like-minded others to replace the connections they previously had. While transient (sometimes called “situational”) loneliness is unpleasant, it’s an inherent part of being human. Psychologists don’t see this type of loneliness as problematic; rather, it’s a signal that change is needed, much in the same way that we grab that glass of water when thirst strikes or wander into the kitchen when our guts send up hunger signals. With loneliness, the action needed is to invest time and effort into relationship (re)building: the sooner, the better (Wigfield, 2024).

The problem for our individual and collective mental health occurs when this state continues on for a long time: months or even years, to become a chronic trait of a person. This type of loneliness is the one that damages spiritual, mental, emotional, and physical health. It is the type in which people begin to think negatively about themselves (e.g., “What’s wrong with me that I can’t seem to get good relationships going?”) and that others are thinking negatively about them, which can lead to a lonely self-fulfilling prophecy. It is this latter type of loneliness that is more challenging to deal with in the therapy room (Wigfield, 2024).

Psychological, societal, and existential loneliness

Dr. Jeremy Nobel’s book on loneliness (2023) talks about three categories of loneliness: psychological, societal, and existential. He acknowledges that a person may have more than one type at a time, but stresses that it is important to assess which type is (most) challenging a given client, so that it can be addressed properly, as each type requires different interventions.

Psychological loneliness (also referred to in other typologies as “internal”, “intimate”, or “emotional” loneliness) is what most people are feeling when they say they are lonely. It is that sense of wishing for reliable, authentic connection to a specific someone, another person they can trust, to whom they can tell their troubles, and who “has their back” when things get tough: someone the lonely one can care about. This psychological state is tinged – if not permeated – with sadness, fear, shame, regret, anger, guilt, or self-doubt.

The challenge in this state is that, because of insecure early attachments to caregivers, such individuals are fearful of developing close relationships and instead develop insecure attachments which are inadequate or unstable. Someone who is around people all day long and who seems to have friends may still not find that there is someone among all the people they relate to whom they can genuinely trust or confide in. Even while enjoying great popularity, such an individual may have a psychological fear of opening up emotionally to any of the friends that they have. This is the “lonely in a crowd” situation. Nobel comments that the question people having this type of loneliness might ask is, “Where are my people?” (Nobel, 2023; Murthy, 2020).

A screening question for loneliness

A quick way to gauge if a client may be lonely is to simply ask how often they feel lonely, although some clients may prefer not to admit that they are lonely, and some do not seem to be aware that they are. The question and response options can be:

How often do you feel lonely?

___ Often/always

___ Some of the time

___ Occasionally

___ Hardly ever

___ Never

If they tick any of the top three boxes (e.g., “often/always”, “some of the time”, or “occasionally”) they are probably lonely, because it is a common emotion, and people may underemphasise it due to the stigma associated with it.

Societal loneliness (also referred to as “social” or “relational” loneliness) occurs when people have a keen sense that they simply do not fit in or belong, or that they are being systemically excluded. This describes the experience of being rejected or at least uninvited by a peer group, work colleagues, neighbours, or society at large. Immigrants who come to live in a community that is very different from the one they left behind may be glad to have escaped the persecution or conflict in their home country, but they may wonder how they can weave themselves into the fabric of the new country, with its different language, culture, and informal “rules” for how to develop and maintain relationships. In a similar vein, minoritised groups may have grown up in the city in which they currently live but feel excluded or alienated from the things that that community majority seems to hold dear. We can imagine sufferers of this type of loneliness coming into, say, a town hall meeting and, upon seeing the room full of people, asking, “Am I welcome?” “Were they expecting people like me to come?” “Do I fit in here?” “Is there a seat for me here?” (Nobel, 2023; Murthy, 2020).

This type of loneliness is depicted in the movie, “Hidden Figures”, based on the life of the brilliant Black mathematician Katherine Johnson, who went to work for NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration) in the United States in 1953. At the time (before the U.S. civil rights movement of the 1960s), there was huge individual and systemic discrimination against both Black people and women. The movie shows Johnson being snubbed, put down, and excluded at every turn, even though she is making a huge contribution to the effort to put men into space. The real Katherine Johnson said that she didn’t experience that much discrimination, although she acknowledged that it was there (Lang, 2017). The movie heightens this aspect dramatically, and the viewer can well imagine Katherine asking herself, “Is there room for me here when I am not even allowed in the briefing room and I am supposed to walk ten minutes to another building where ‘coloured’ people go to the bathroom?” (Nobel, 2023)

Existential loneliness (which Vivek Murthy refers to as “collective loneliness”) can be thought of as the unmet need to connect with a purpose, something larger than ourselves; it can occur in the presence of even closely connected others if we hunger for a network to share purpose and interactions related to that. The world’s religions have long touted the happiness and sense of meaning that obtains from accepting their version of the Absolute, the Divine. Studies show that those who do address existential angst tend to have more meaning and purpose in their lives; they tend to be happier and more resilient. They are more tolerant of and less vulnerable to other kinds of loneliness. It would seem that knowing one’s place in the universe may reduce the discomfort of relatively lower levels of intimate connection with other human beings, as such individuals experience little or no pain when alone or in unfamiliar social settings: in other words, less loneliness (Murthy, 2020; Nobel, 2023).

The problem for many in the modern world is that they want a life of purpose, meaning, and connection, but – in fear of the ultimate disconnection of death – engage myriad devices for distracting themselves from death anxiety and end up disconnecting from themselves, which constrains their connections with others. Many in contemporary individualistic cultures do not have a spiritual holding and thus go into the void of existential loneliness (Nobel, 2023). The question one might ask with this type of loneliness could be, “Who am I, and what matters to me?” Extinguishing this type of loneliness requires connection with self, then with the “something more”.

Any type of loneliness engenders emotional pain for the person experiencing it, and as we will see in future articles, leads to poorer health outcomes, so alleviating it is important.

Conclusion

In this article, we offered facts about loneliness, differentiated between loneliness and isolation and between loneliness and solitude. We noted that loneliness can be transient or chronic (the latter being more worrying) and explained the three types of loneliness: psychological, societal, and existential. In the next article of this series, we will discuss the impacts of loneliness, the demographics and life situations associated with it, and what it costs. The final article will suggest approaches that are likely to be effective in each of the principal “domains” or “territories” of loneliness.

Key takeaways

- Loneliness is increasing globally.

- Loneliness is a subjective state of feeling a discrepancy between the quality and quantity of relationships one has and those desired.

- Isolation is an objective state of not being around other people.

- Solitude is state of aloneness sought by creatives, mystics, and others to deepen introspection and creativity and enhance connection with the divine.

- Loneliness can be transient or chronic.

- The three main types of loneliness are psychological, societal, and existential.

Questions therapists often ask

Q: How do I differentiate “being alone” from clinical loneliness in assessment?

A: The article makes it clear that loneliness isn’t about headcount but about disconnection. Clients describe a mismatch between the relationships they want and the ones they feel they have. In practice, explore perceived adequacy and quality of relationships rather than frequency of social contact. Someone with a wide network can still feel deeply lonely if those connections feel thin or unsafe.

Q: What signals should make me think a client’s loneliness is chronic rather than situational?

A: Chronic loneliness shows up as a long-running pattern of disconnection, a sense of “outsiderness,” and a more entrenched worldview that relationships aren’t accessible or dependable. Situational loneliness tends to link clearly to a transition or loss and shifts more readily as circumstances change. Chronic presentations often come with rigid beliefs about the self and others.

Q: How do I explore loneliness without clients feeling pathologised or embarrassed?

A: The article frames loneliness as a universal human experience, so normalisation is a safe entry point. You can ask about the client’s sense of belonging, closeness, and satisfaction with relationships rather than using the word “loneliness” immediately. Let them set the language once the dynamic is named.

Q: What’s the clinical value of distinguishing emotional from social loneliness?

A: Emotional loneliness points to absence of intimate, trusted relationships; social loneliness points to lack of broader community or group belonging. Separating the two helps you target interventions—emotional loneliness may call for attachment-focused work, social loneliness for re-engagement with community roles or group contexts. Clients often benefit simply from understanding which type is dominating their experience.

Q: How should I respond when a client minimises their loneliness even though it’s clearly impacting functioning?

A: The article highlights shame as a key barrier. Instead of confronting the minimisation directly, approach it through curiosity: explore how they learned to cope by downplaying needs, or what it would mean to acknowledge the pain more fully. Gentle pacing matters—loneliness carries vulnerability, and pushing too hard can reinforce the very withdrawal you’re trying to treat.

References

- AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare). (2024). Social isolation and loneliness. AIHW. Retrieved on 15 April, 2025, from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/mental-health/topic-areas/social-isolation-and-loneliness

- Lang, K. (2017). Hidden figures: History vs. Hollywood. History vs. Hollywood. Retrieved on 14 April, 2025, from: https://www.historyvshollywood.com/reelfaces/hidden-figures

- Murthy, V. (2020). Together: Loneliness, health and what happens when we find connection. London: Profile Books Ltd. eISBN 9781782835639

- Nobel, J. (2023). Project unlonely: Navigate loneliness and reconnect with others. Great Britian: Headline Home (an imprint of Headline Publishing Group). eISBN: 978 1 4722 8704 5

- Reynolds, S. (2024). The loneliness problem: A guided workbook for creating social connection and ending isolation. New York: Chartwell Books, an imprint of the Quarto group. ISBN: 976-0-7858-4427-3

- Wigfield, A. (2024). Loneliness for dummies. Hoboken, New Jersey, USA: John Wiley and Sons, inc. (ePDF); ISBN 978-1-394-22933-8 (ePub)