Self-harm, or non-suicidal self-injury, takes numerous forms and serves various functions. This article outlines the forms and reviews the Four-Function Model.

Related articles: Non-Suicidal Self-Injury: Prevalence, Risk and Protective Factors.

Jump to section

Introduction and background

Today we begin a series of articles about self-harm. Non-suicidal self-injury, or NSSI, is defined as “intentional self-inflicted damage to the surface of the body of a sort likely to induce bleeding, bruising, or pain” on at least five days in the past year, where the behaviour is not socially sanctioned (e.g., tattooing, piercing) and is performed without suicidal intent (APA, 2022).

It is not a new phenomenon. Anthropological and historical evidence shows that various forms of self-injury have existed for centuries, sometimes embedded in religious or cultural practices, such as ritualistic scarification or flagellation (Favazza, 1998). However, modern clinical recognition of self-harm as a distinct psychological concern dates back to the mid-20th century, when psychiatrists began describing repetitive self-cutting among young women in psychiatric hospitals (Graff & Mallin, 1967).

In the 1980s and 1990s, research expanded significantly, shifting from viewing self-harm as primarily a symptom of borderline personality disorder to recognising its presence across a wider range of diagnoses and among community samples. By the early 2000s, epidemiological studies revealed that self-harm was far more prevalent in adolescents and young adults than previously recognised. For example, Muehlenkamp et al (2012) estimated that 17–18% of adolescents and around 6% of adults in the general population report a history of NSSI.

Today, self-harm is understood as a multifaceted behaviour with multiple potential functions, including emotion regulation, self-punishment, communication of distress, and reduction of dissociation (Klonsky, 2007). It is also increasingly studied as a transdiagnostic marker of distress and vulnerability to later suicidal behaviour.

Common forms of self-harming behaviour

Self-harm can take many forms, varying by individual preference, cultural context, and accessibility of means. While cutting is most frequently reported, research identifies a wide array of behaviours that constitute NSSI. Common methods include:

Cutting

Cutting the skin with sharp objects (e.g., razors, knives, or broken glass) is consistently reported as the most prevalent form of NSSI across adolescent and adult populations (Whitlock et al., 2006). The arms, thighs, and abdomen are common sites, often chosen because they can be easily concealed. Cutting may serve functions such as releasing emotional tension, alleviating numbness, or punishing oneself.

Burning

Burning the skin using cigarettes, lighters, or heated objects is another common form. Although less prevalent than cutting, it is reported by a significant subset of individuals. Burning tends to produce more visible scarring and may carry specific symbolic meanings, such as cleansing or punishment (Nock, 2010).

Scratching, banging, or hitting

Some individuals engage in scratching their skin to the point of bleeding, or hitting and banging themselves (e.g., punching walls, striking their own head). These behaviours can be impulsive, often occurring during episodes of acute distress or anger. Self-biting and hair-pulling may also fall into this category (Muehlenkamp & Gutierrez, 2007).

Interfering with wound healing

Reopening wounds or deliberately preventing healing (e.g., through picking or rubbing) is another self-harm method. This form may serve to prolong the experience of injury, reinforce feelings of control, or intensify visible markers of internal pain (Klonsky, 2007).

Ingesting substances or self-poisoning (without suicidal intent)

Although deliberate self-poisoning is sometimes associated with suicide attempts, some individuals ingest non-lethal doses of harmful substances, medications, or toxic agents without suicidal intent. This form is more commonly included under the broader UK/European definition of self-harm (employed as an umbrella term encompassing all intentional acts of self-injury and self-poisoning, regardless of suicidal intent) rather than the narrower NSSI construct (used by North American researchers to signify non-suicidal intent) (Hawton et al., 2012).

Patterns and characteristics

Research indicates that most individuals who self-harm use more than one method over time. Whitlock et al. (2008) found that adolescents engaging in NSSI often reported multiple methods, with cutting, scratching, and banging being the most common. Gender differences have also been noted: while both males and females self-harm, females are more likely to cut, whereas males are somewhat more likely to hit themselves or engage in riskier external behaviours (Muehlenkamp et al., 2009).

The frequency and severity of self-harm vary widely. Some individuals may experiment once or twice, while others develop chronic patterns of self-injury. Studies show that repetition increases risk for escalation and for transition to suicidal behaviour, underscoring the importance of early identification and intervention (Whitlock et al., 2011).

While the above behaviours describe the “what” of NSSI, we are unlikely to help clients find alternative behaviours until we understand why they do it: what functions it serves.

Functions of self-harming

A clinical overview of NSSI functions

Nonsuicidal self-injury refers to the deliberate damage of one’s own body tissue without suicidal intent and distinct from suicide attempts, which involve at least some intent to die. This distinction matters clinically because the same behaviour (e.g., cutting, burning) can occur for very different reasons, and treatment should be tailored to those reasons rather than to the method alone. At the same time, NSSI and suicidal behaviour can and do co-occur, and NSSI elevates later suicide risk, so careful assessment of intent and risk is essential (Ammerman et al, 2025).

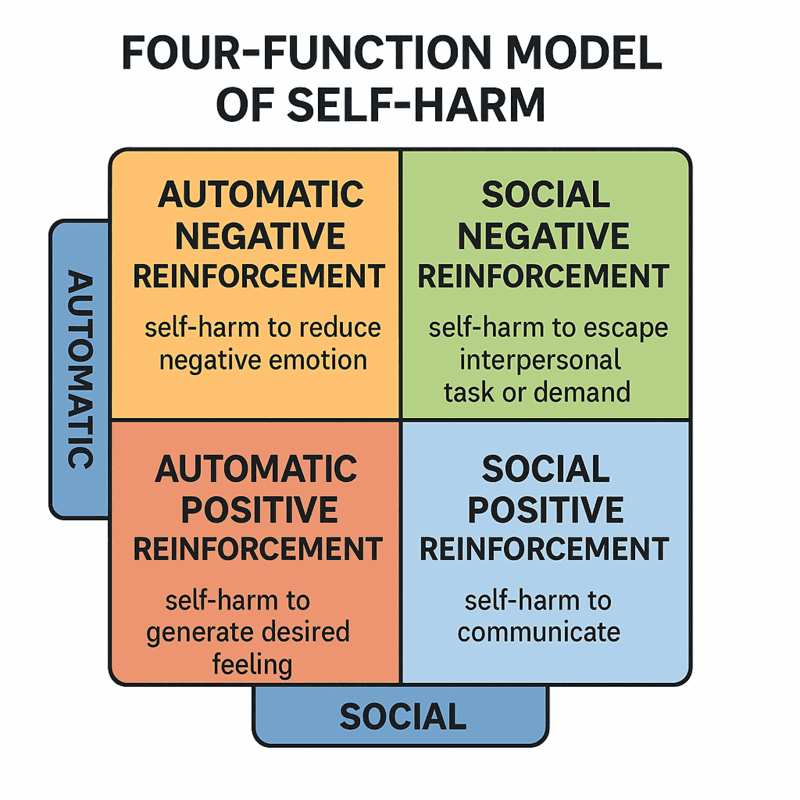

Two complementary lines of evidence shape contemporary understanding of why people self-injure. The first is the well-validated Four-Function Model (FFM – see figure below: Four Function Model of Self-Harm), which proposes that NSSI is maintained by reinforcement processes operating at two levels – automatic (intrapersonal) and social (interpersonal) – and in two directions – negative (removing something aversive) and positive (adding something desired).

Intrapersonal negative reinforcement (reducing or escaping intense aversive emotion, physiological arousal, or unwanted thoughts) is the single most frequently endorsed function; intrapersonal positive reinforcement (generating desired feelings, e.g., relief, feeling “something” when numb) is also common. Social negative reinforcement captures attempts to avoid interpersonal demands or punishments, while social positive reinforcement includes efforts to communicate distress or elicit care. Together, these four functions are supported across adolescent and adult samples and help clinicians map specific behaviours to specific contingencies (Nock & Prinstein, 2004).

The second line of evidence comes from functional inventories and synthesis studies showing that diverse self-reported motives cluster into two broad families: intrapersonal (emotion regulation, anti-dissociation, self-punishment, anti-suicide) and interpersonal (communication, influence, boundary setting, peer bonding). Klonsky and colleagues’ Inventory of Statements About Self-Injury (ISAS) operationalises many of these motives, and subsequent work demonstrates that a two-factor structure – internal vs. social – captures most variance across samples. Large meta-analyses (that is, studies of studies) find that intrapersonal functions predominate for those who self-harm, with affect regulation the most frequent reason reported, while a substantial minority also endorse social motives (Klonsky et al, 2015; Taylor et al, 2017).

Intrapersonal (automatic) functions

Affect regulation/relief. By far the most common function is to reduce overwhelming affect (e.g., shame, anger, anxiety) or physiological arousal. In behavioural terms, the temporary relief that follows NSSI negatively reinforces the behaviour, increasing the likelihood of repetition under similar emotional conditions. This function dovetails with the Experiential Avoidance Model, which frames NSSI as a rapid (but ultimately costly) strategy to escape or dampen aversive internal states when emotion regulation capacity is overtaxed (Taylor et al, 2017).

Anti-dissociation/feeling generation. When people feel numb, unreal, or detached, NSSI can serve to restore a sense of presence or allow them to “feel something,” often described as a way to counter dissociation. Here, the immediate experience (pain, blood, seeing injury) provides intrapersonal positive reinforcement – adding a desired sensation or clarity (Brown et al, 2022).

Self-punishment and moral emotion regulation. For some, self-injury functions as self-directed punishment linked to intense guilt, shame, or self-criticism. In these cases, NSSI may temporarily satisfy rigid internal rules (“I deserve pain”), reduce self-condemnation momentarily, or symbolically atone – again trading short-term relief for longer-term harm. Meta-analytic and daily-life studies highlight the salient role of self-evaluative emotions in the hours surrounding NSSI (Brown et al, 2022).

Anti-suicide. Paradoxically, some individuals report using NSSI to interrupt or resist escalating suicidal urges – “hurting myself to avoid killing myself.” Although not universal, this function appears in both clinical reports and measurement models and underscores why intent must be assessed directly rather than inferred from method alone (Brown et al, 2022).

Interpersonal (social) functions

Communication and social signalling. People also use NSSI to make internal distress outwardly visible when they lack words, skills, or safe relationships to express it directly. The behaviour can function as a high-salience signal that mobilises attention, care, or protection, especially in contexts where subtler bids have failed. This is not “attention-seeking” in the pejorative sense; it is an attempt – albeit risky and costly – to meet legitimate interpersonal needs. Consistent with the Four-Function Model, social positive reinforcement is less frequently endorsed than intrapersonal motives, but still common across studies (Hepp et al, 2020; Nock & Prinstein, 2004).

Avoidance, boundaries, and influence. NSSI may also help the person avoid perceived punishments or demands (social negative reinforcement), create interpersonal distance, or set boundaries when direct assertion feels unsafe. In some relationships, the behaviour can alter power dynamics or interrupt conflict cycles – again at high personal cost and with significant relational risks (Nock & Prinstein, 2004).

When functions vary – and why that matters

Importantly, individuals often endorse multiple functions, and the dominant function can shift across time, contexts, and relationships. Momentary-assessment research shows that emotional states fluctuate in the hours before and after NSSI, with patterns broadly consistent with intrapersonal negative reinforcement (e.g., spikes in negative affect preceding NSSI, followed by short-lived decreases). Evidence for interpersonal contingencies in daily life is emerging but is less consistent – likely because interpersonal events are harder to capture in “in the moment” sampling. These nuances matter: intrapersonal motives are associated with higher frequency and persistence over time compared with purely interpersonal motives, guiding where clinicians should focus early intervention (Hepp et al, 2020; Coppersmith et al, 2021).

Integrative models

The above descriptions of the functions of NSSI seem clear, but we still face the question: how do people arrive at NSSI as a coping strategy in the first place? A broader theoretical model, the Experiential Avoidance Model, emphasises short-term escape from unwanted emotion utilised in the context of skills deficits and reinforcement learning. Cognitive-emotional models add the role of NSSI-specific outcome expectancies (“this will calm me down”), self-efficacy beliefs about emotion control, and attentional biases that make self-injury more accessible under stress. Putting all of those together, we see how these additional approaches portray NSSI as a learned, self-reinforcing solution to problems of emotion regulation and social communication – “effective” in the moment but costly for health, safety, and relationships (Hasking et al, 2017; Chapman et al, 2006).

Clinical implications

Function-informed care begins with assessment that maps each person’s behaviour to its likely contingencies. When affect regulation predominates, interventions that build alternative regulation strategies (e.g., distress tolerance, grounding, progressive muscle relaxation) and directly reduce experiential avoidance are central; when self-punishment themes are present, clinicians target shame, rigid moral beliefs, and self-criticism (e.g., compassion-focused or cognitive restructuring approaches). Where interpersonal signalling is primary, therapy emphasises safer communication, boundary-setting, and problem-solving, often with family or partner involvement to alter the social contingencies that inadvertently maintain NSSI. Evidence from meta-analyses and daily-life studies supports prioritising intrapersonal functions early, given their prevalence and association with chronicity, while not neglecting the interpersonal context in which NSSI is embedded (Taylor et al, 2017; Halpin & Duffy, 2020).

Finally, clinicians should hold two truths simultaneously: first, NSSI serves genuine psychological and social functions – people are doing the best they can with the tools they have; and second, those functions can be met more safely and sustainably. A collaborative, validating stance that takes functions seriously, coupled with skill development and environmental change, offers the best chance of reducing reliance on NSSI while addressing the problems it temporarily solves (Bently, Nock, & Barlow, 2014).

Conclusion

Self-harming behaviour, or NSSI, is best understood as a complex, multifaceted phenomenon. While it has been recognised in both cultural rituals and clinical contexts throughout history, it is widely acknowledged today as a significant mental health concern, particularly among adolescents and young adults. In this article, we have identified common self-harming behaviours and discussed the functions of self-harming behaviour.

By appreciating both the common methods of self-harm and the underlying motivations for engaging it, clinicians, educators, and policymakers can more effectively address the needs of those at risk. In the next article in this series, we look at NSSI’s prevalence, the risk and protective factors related to it, and also the warning signs that it may be occurring.

Key takeaways

- Anthropological and historical evidence shows that various forms of self-injury have existed for centuries as cultural and religious rituals, but today, self-harm is understood as a multifaceted, multiple-function behaviour which is of high clinical concern.

- NSSI can take many forms, including cutting (most common); burning; scratching, banging, or biting; interfering with wound healing; or ingesting toxic substances.

- NSSI has many functions, which can be categorised according to the Four-Function Model, wherein the reason for self-harming can be plotted on a matrix as either automatic (intrapersonal) or social (interpersonal) (on one dimension) and either positively or negatively reinforcing (on the other dimension).

- The clinical implications of the various forms and functions are that clinicians need to understand what function it serves for the client so that treatment can be tailored individually to the client.

Questions therapists often ask

Q: How do I distinguish NSSI from suicidal behaviour when a client’s intent seems ambiguous?

A: Anchor your assessment in function, not the severity of the injury. The article emphasises that NSSI is carried out without suicidal intent and typically serves regulatory, communicative, or self-punitive purposes. Ask directly about perceived purpose, desired outcomes, and expectations of the act. When clients describe wanting to feel “relief,” “control,” or “punishment,” you’re likely in NSSI territory; when they describe wanting to die or escape life permanently, you shift into suicide-risk intervention.

Q: Clients often minimise their NSSI. What should I focus on to understand risk without over-relying on the physical appearance of injuries?

A: Prioritise patterns, functions, and escalation signals. The article notes that injury severity alone isn’t a reliable proxy for risk. Track frequency, situational triggers, the client’s emotional state beforehand, and how effective the behaviour feels to them. A stable method that suddenly changes, or a function that stops “working,” often signals increased vulnerability even if wounds look superficially mild.

Q: When a client uses multiple forms of NSSI, how should I interpret that clinically?

A: Multiple methods generally indicate broader dysregulation and a more entrenched coping system. The article highlights that clients may move between cutting, burning, hitting, scratching, or interfering with wound healing depending on what relief they seek or what they can access in the moment. Your job is to map the function of each form and identify the emotional or interpersonal needs each method attempts to address.

Q: How can I talk about the functions of NSSI without making clients feel analysed or pathologised?

A: Keep the focus on lived experience, not labels. The article frames NSSI functions—affect regulation, self-punishment, interpersonal signalling—as adaptive solutions to overwhelming internal states. Reflect this stance in your language. Instead of “Your behaviour serves an intrapersonal function,” ask “What does this help you feel or avoid in the moment?” It normalises exploration and reduces shame.

Q: What’s the clinical significance when NSSI becomes an interpersonal communication tool?

A: It suggests unmet relational needs and a breakdown in safer communication pathways. The article notes that some clients use NSSI to elicit care, express distress they can’t verbalise, or influence interpersonal dynamics. Rather than treating this as manipulation, frame it as a signal: the client is showing you where communication skills or attachment-related work is required. Building alternative communication strategies becomes central to treatment.

References

- Ammerman, B. A., Burke, T. A., O’Loughlin, C. M., & Hammond, R. (2025). The association between nonsuicidal and suicidal self-injurious behaviors: A systematic review and expanded conceptual model. Development and Psychopathology, 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1017/S095457942500001X

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th Ed., Text Revision). Washington, DC: Author.

- Bentley, K. H., Nock, M. K., & Barlow, D. H. (2014). The Four-Function Model of Nonsuicidal Self-Injury: Key Directions for Future Research. Clinical Psychological Science, 2(5), 638-656. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702613514563

- Brown, A. C., Dhingra, K., Brown, T. D., Danquah, A. N. & Taylor, P.J. (2022). A systematic review of the relationship between momentary emotional states and nonsuicidal self-injurious thoughts and behaviours. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 95, 754–780. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12397

- Chapman, A. L., Gratz, K. L., & Brown, M. Z. (2006). Solving the puzzle of deliberate self-harm: The experiential avoidance model. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 371-394.

- Coppersmith DDL, Bentley KH, Kleiman EM, Nock MW, Variability in the Functions of Nonsuicidal Self-Injury: Evidence From Three Real-Time Monitoring Studies, Behavior Therapy, Vol. 52(6), 2021, pp 1516-1528, ISSN 0005-7894, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2021.05.003.

- Favazza AR. The coming of age of self-mutilation. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1998 May;186(5):259-68. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199805000-00001. PMID: 9612442.

- Graff, H., & Mallin, R. (1967). The syndrome of the wrist cutter. American Journal of Psychiatry, 124(1), 36–42. PMID: 6025949 DOI: 10.1176/ajp.124.1.36

- Halpin SA & Duffy NM. (2020). Predictors of non-suicidal self-injury cessation in adults who self-injured during adolescence, Journal of Affective Disorders Reports, Vol. 1, 2020. 100017, ISSN 2666-9153, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadr.2020.100017.

- Hasking, P., Whitlock, J., Voon, D., & Rose, A. (2017). A cognitive-emotional model of NSSI: using emotion regulation and cognitive processes to explain why people self-injure. Cognition and Emotion, 31(8), 1543-1556. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2016.1241219

- Hawton K, Saunders KE, O’Connor RC. Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. Lancet. 2012 Jun 23;379(9834):2373-82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60322-5. PMID: 22726518.

- Hepp J, Carpenter RW, Störkel LM, Schmitz SE, Schmahl C, & Niedtfeld I, (2020). A systematic review of daily life studies on non-suicidal self-injury based on the four-function model, Clinical Psychology Review, Vol. 82, 2020,101888. ISSN 0272-7358 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101888.

- Klonsky, E. D. (2007). The functions of deliberate self-injury: A review of the evidence. Clinical Psychology Review, Vol. 27(2), pp. 226–229. ISSN 0272-7358, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2006.08.002.

- Klonsky, E.D., Glenn, C.R., Styer, D.M. et al. (2015). The functions of nonsuicidal self-injury: converging evidence for a two-factor structure. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 9, 44 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-015-0073-4

- Muehlenkamp, J. J., Claes, L., Havertape, L., & Plener, P. L. (2012). International prevalence of adolescent non-suicidal self-injury and deliberate self-harm. Child and adolescent psychiatry and mental health, 6, 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1753-2000-6-10

- Muehlenkamp, J. J., Engel, S. G., Wadeson, A., Crosby, R. D., Wonderlich, S. A., Simonich, H., & Mitchell, J. E. (2009). Emotional states preceding and following acts of non-suicidal self-injury in bulimia nervosa patients. Behaviour research and therapy, 47(1), 83–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2008.10.011

- Muehlenkamp, J. J., & Gutierrez, P. M. (2007). Risk for suicide attempts among adolescents who engage in non-suicidal self-injury. Archives of suicide research : official journal of the International Academy for Suicide Research, 11(1), 69–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811110600992902

- Nock M. K. (2010). Self-injury. Annual review of clinical psychology, 6, 339–363. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131258

- Nock MK & Prinstein MJ. (2004). A Functional Approach to the Assessment of Self-Mutilative Behavior, Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 2004, Vol. 72, No. 5, 885– 890 0022-006X/04/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.885

- Taylor, P., Jomar, K., Dhingra, K., Forrester, R., Shahmalak, U., & Dickson, J. M. (2017). A meta-analysis of the prevalence of different functions of non-suicidal self-injury. Journal of Affective Disorders, 227, 759–769. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.073

- Whitlock, J., Eckenrode, J., & Silverman, D. (2006). Self-injurious behaviors in a college population. Pediatrics, 117(6), 1939–1948. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-2543

- Whitlock, J., Muehlenkamp, J., & Eckenrode, J. (2008). Variation in nonsuicidal self-injury: identification and features of latent classes in a college population of emerging adults. Journal of clinical child and adolescent psychology: the official journal for the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, American Psychological Association, Division 53, 37(4), 725–735. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410802359734

- Whitlock, J, Muehlenkamp J, Purington A, Eckenrode J, Barreira P, Abrams GB, Marchell T, Kress V, Girard K, Chin C, & Knox K. (2011). Nonsuicidal Self-injury in a College Population: General Trends and Sex Differences, Journal of American College Health, 59:8, 691-698.